02 Aug A Common Voice from the East and the West: Why the Middle Path is Worth Our Attention

As sentient beings we are endowed with the gift and curse of the desire to make sense of our experiences and construct a personal narrative that enables us to deal with the challenges of life. In the “insta-gratification” world we live in today there is no shortage of sellers of short-term wisdom and half-philosophies in the form of pundits, Instagram celebrities, and Facebook priests. While there may be some value in the watered-down, cookie-cutter and prescriptive ideas insofar as they make us feel good momentarily, true lasting insight remains elusive for most of us. So how do we separate the signal from the noise?

Identifying true insight among the dram of the superficial is a difficult task. I believe that the answer is to be found in those ideas that embrace the complications of existence (rather than deny it), stray from the easy path of prescriptive ideology, and are able to appreciate the need for reconciling the personal narrative with the global human condition. It is perhaps within this tension of the individual and the collective, the free will and inevitable constraints of circumstances, and competing desires, motivations and intentions that true wisdom can be found. The reality is that even such grand philosophies are human creations and subject to temporal (and dare I say mortal) constraints and are doomed to failure, and rightly so, for otherwise life would be too uninteresting to endure; however, the span over which they are coherent and the extent to which they are able to reconcile existential absurdities can be breathtakingly beautiful. There are many enduring and profound philosophies of the aforementioned variety that deserve our attention.

Being a child of two worlds: the East and the West, having spent considerable parts of life living there (at the time of writing it is evenly split), I am inherently drawn to the wisdom in multicultural perspectives. I believe no culture has a monopoly on the truth and indeed, I have found that the litmus test to wisdom is how insights on the human condition can be transplanted across cultures (to the extent that is possible). This is one of the reasons I strongly advocate traveling (not to be confused with vacationing or even the longer “staycationing”) where one is truly able to transcend the prejudiced, albeit comforting, concepts of nationality, language, mother-culture and so forth. This is because these types of familiarity frequently build into it the notion of “us” and “them”, but I digress. If for nothing else but aesthetics alone, I would vouch for studying philosophies and cultures of different spatiotemporal geographies and to understand their commonalities and distinctions as they can be spectacularly eye-opening.

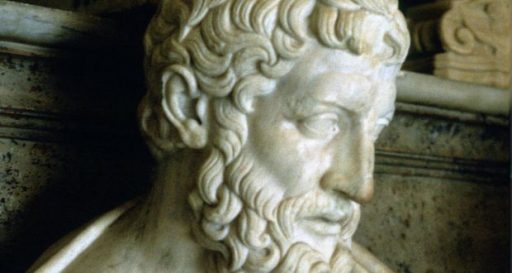

Bust of Epicurus: A Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original (Courtesy: Wikipedia)

The Seated Buddha from Gandhara dated to the 2nd or 3rd century CE. (Courtesy: Wikipedia)

In this article I would like to explore two figures who have been tremendous teachers to me. Siddhartha Gautama of ancient India (circa 560 BCE) and Epicurus of ancient Greece (born 341 BCE) were profound thinkers of their time and had much to say about the human condition and how to conduct our lives. Indeed, they were quick to identify that misery and confusion seems to be a common human experience that we need to be able to handle better throughout our lifetime and, possibly, even transcend. A striking commonality between Epicureanism and Buddhism is found in their practical approach to living life; the middle path that they advocate is about harmony and rejecting either extremes of self-absorption or self-abnegation. Their conceptualizations are expectedly vastly different and also worth studying as they offer two lenses to survey the landscape of the human narrative. In what follows, I will attempt to present some ideas of these philosophies in a simplified manner. I would strongly urge the reader to take their time and consult the many excellent books and academic articles that are readily available. A deep dive is a must and it is arduous, but as the saying goes “no pain, no gain”.

Of the two works of philosophy, Epicureanism is perhaps the most accessible to a western audience as it grew out of classical western culture which informs much of the West today. Being of Athenian descent, Epicurus favored meticulous taxonomy in his construction of the human condition. His universe was strictly a physical one, rejecting all paraphysical possibilities like life after death, and relying on an atomistic description that drew heavily on Democritus. Brilliantly, however, he recognized that determinism, which inevitably followed (classical) atomism, was incompatible with the notion of the human free will. To account for this, he allowed for “swerving” in atomic trajectories due to the possibility of randomness – an idea far ahead of its time and only truly accommodatable within quantum physics.

Cosmology aside, Epicurus’ practical observations on the human condition were remarkably incisive. His vision for sentient existence is one which is free from long-term fear and physical pain. This could be achieved by cultivating a lifestyle based on a nuanced understanding of pleasure and pain and their interplay with the human psyche. As an important aside, it is worth mentioning that Epicurus’ ideas were a subject of controversy and faced much hostility from early Christianity and suffered through infamy during the middle ages as a benefactor of the worst kind of hedonists. It is only in the seventeenth century and during and after enlightenment that his work was given its due consideration by preeminent scholars like Robert Boyle, John Locke, Karl Marx and Thomas Jefferson. Apparently, he was liked by people who would strongly disagree with one another, giving us some reason to believe in the worthiness of his insights.

Epicurus described three types of desires which are the sources of pleasure and pain: natural necessary desires, natural but unnecessary desires and empty desires. Understanding the effect these types of desires has on the human psyche and accounting for them while making life choices is the key. According to Epicurus, natural necessary desires are essential for happiness, physical well-being and vitality – life itself. These types of desires include things like food and shelter. They are easy to satisfy, and the pleasures derived from them are limited. Excesses here lead to unnecessary desires like luxury goods and so forth. Moderation of unnecessary but natural desires allows the mind to be freed from pointless agitation due to their unfulfillment. Other types of natural but unnecessary desires include those derived from sensory activations such as pleasurable odors, food and drink, sex etc. The last category that constitutes unquenchable desires is the most dangerous – no matter how much one gets, one wants more like power, wealth, and fame. Pursuing these types of desires is to be avoided because of their inherent destructive qualities that does nothing but perturb the mind and cause continuous pain. According to Epicurus the pleasures derived from these desires are not natural and inculcated by a malfunctioning society.

Epicurus further classifies pleasures into two types: kinetic and static. The former are the types of pleasure (derived frequently from the natural but unnecessary variety of desire) that arises while actually fulfilling a desire and involves active stimulation of the senses. Once achieved, the satisfaction goes away quickly and the pain of wanting to fulfill them returns again. Static pleasures, on the other hand, do not have this impermanent quality. For Epicurus, friendship and philosophy are such pleasures as they both induce the kind of joys that never abate but only accumulate. Epicurus leaves it to us to decide what is the optimum combination of pleasures derived from desires for ourselves. His central message is that rejecting natural desires is just as futile as it is to pursue unnatural socially fabricated ones. By balancing our desires and activities we are able to achieve harmony within ourselves.

Much like most eastern philosophes, Siddhartha Gautama’s vision for human existence also revolves around harmony and he was able to expound on it in strikingly beautiful ways. Siddhartha’s own life is ample illustration of the remarkable nature of Buddhist thought. Born a prince, he was overcome with extreme existential crisis after witnessing three poignant instances of the human condition: aging, death and disease. Finally, after he witnessed the fourth condition of wisdom due to an encounter with a sage, he found some peace and decided to leave the comforts of home, family, and rank to pursue monasticism for deeper truths. It was rather ironic that despite practicing and mastering all known forms of asceticism and spiritual practices he realized they do not really lead to the kind of insights needed for inner peace. Central to attaining Buddhahood was his realization that transcendence from the human condition required first to experience the human condition! The point was to understand the network of choices and consequences that might enable us to live a life that is in tune with the highest ideals of sentient existence – this insight plays an essential role in the Buddha’s middle path.

In very simple terms the middle path suggested by the Buddha appears to be just a set or recommendations (known as the Noble Eightfold Path) that minimizes overall harm to all of creation including oneself. However, these recommendations are not prescriptive and actually require careful thought and discipline. The reason is that intention is profoundly important in Buddhist philosophy and just avoiding potentially harmful action is not good enough. Active forms of control are also not recommended since it requires unnecessary amounts of force and is not practical. Passivity and “flow” in thought as well as action are central to maintaining a harmonious existence. In order to understand Siddhartha’s middle path, we have to spend some time appreciating his cosmology. This is by no means an easy task as some of the concepts are completely alien to classical western modes of thinking. I assure you, however, they are unparallelly gorgeous and will be worth your while.

The quintessence of Buddhism derives from rejection of both eternalism and annihilationism. Eternalism is most easily understood via the western notion of the soul. That is there is some non-physical component within us that survives our physical destruction or death. Annihilationism is similarly the idea that everything is describable in physical terms and therefore once the physical body ceases vital functioning complete termination is the only possibility, i.e., death is final. Siddhartha’s view is that both of these extremes fundamentally misunderstands the nature of creation as it inevitably focuses on the “I” – and there is simply no such thing. That is, the Buddha rejects both the possibility of the soul and lack of it! Although at first glance this might seem incoherent, it should be not very hard to see that what he is rejecting is actually the very premise of individuality itself.

Central to understanding Buddhism is the idea of a relational identity that we sentient beings frequently mistake to be an absolute identity. This is already quite esoteric and needs further explanation. By absolute identity I mean a differentiated version of the self of the me vs. you type, where a being’s individual existence is independently possible and, in case of sentient beings, endowed with large degrees of agency. Buddhism rejects this point of view. It holds that this type of individualized identity is a complete illusion and arises because the untrained mind is beguiled by sensory perception. Getting caught up in this individualized self leads to egocentric behavior such as pursuit of wealth, power, fame etc. leading to attachment to impermanent and unproductive pleasures and inexorably pain and suffering ensues. The other extreme of self-negation due to annihilationism is just as traumatizing as it reflexively rejects any responsibility we have towards ourselves or others. Indeed, it often leads to the very same types of destructive behavior that arises in egocentric attitudes, albeit from an (apparently) different psychological standpoint.

In Buddhist cosmology, the only type of individuality that we should acknowledge as sentient beings is of the “softer” relational variety which posits identity as the nexus of a network of connections which could be identified with an entity having agency. This diffused being affects and is affected by every connection that is linked to it to varying degrees depending on the strength of the link. All of creation should thus be viewed as a web of connections between different focal points – pull on one thread and it reverberates over the entire network. Incidentally, this network is known as samsara and the intentions (whether actualized or not) contemplated by a sentient being and their consequences is known as karma. Note that while it is tempting to redefine the network in terms of absolute individualized identities and connections between them, this would be incorrect as it would attribute us with far more independence and agency than we can ever have.

Accepting the type of relational identity that Buddhism purports has a spectacular consequence: By virtue of samsara and karma it immediately recognizes a form of collective responsibility – that we are all in this together and the only way to a better reality is if we lift each other. It also hypothesizes that as we gain more enlightenment our sphere of influence increases due to an increase in the strength of the links, ultimately leading to complete coincidental existence with the full network through which moksha (liberation) becomes possible. A rather beautiful, and often overlooked idea of Buddhism, is that the point of enlightenment is not actual liberation from the cycle of life and rebirth but rather to have such an extreme sense of love for all of creation that even given the choice of liberation we choose to come back to help everyone. This is what distinguishes Buddhahood from mere “enlightenment”. The path to increasing our connectivity is prescribed by our dharma (loosely, duty) that is characterized by a set of passive psychological and behavioral recommendations. These are provided to protect us from the double-edged sword of sentience — the greater our degree of perception and control, the greater is our ability to identify with the whole, but so is the ability to go out of tune with our true nature.

It should be plain to see that the type of oneness that is being espoused cannot be understood by becoming a monk and running away from society since loving all creation necessarily means being an active part of it – that is participate in the day-to-day activities of human dharma. Additionally, contrary to popular belief, by detachment it is not meant that we forgo emotions since without it love and, therefore, enlightenment is not possible, but rather we are expected to detach from the desire of specific outcomes and just attend to our karma undertaken in accordance with our dharma. The emphasis is on the process and not the goal.

Though separated by a variety of barriers, and possessing several nuanced differences in their technical constructions, the central practical ideas of the two schools of thought are strikingly similar. Practicing the middle path is a balancing act and requires discipline in cultivating awareness. The optimum path for Epicurus is based on equating the cost or benefits of pursuing different kinds of pleasure so as to minimize long-term pain. For the Buddha minimizing harm requires a conscientious participation in creation for the sake of everyone as well as oneself. Both philosophies vehemently recommend against indulging in extremes of hedonism and asceticism but encourage us to choose for ourselves while still taking responsibility for our actions or karma. Thus, both philosophies delineate a dynamic (by and large) non-prescriptive global vision that fully recognizes and encourages our agency in constructing our path in life. In many ways this type of a non-prescriptive approach is much harder to follow as it does not explicitly fall into the reward-based systems (of the absolute variety: heaven, hell and such) with which we are generally familiar. They are systems of thought that are meant for adults – no coddling, certainty or easy answers. However, their beauty and grace are hard to deny to anyone willing to truly pay attention to their call from over 2000 years ago.

by Ray Ushnish

Ray is a life enthusiast. He was a Fellow at Caltech and Princeton University, specializing in the quantum phenomenology of materials, nonequilibrium statistical mechanics and disordered systems. He is now pursuing entrepreneurial activities in technology. In his free time, Ray avidly pursues the epicurean lifestyle. Socializing with people from all walks of life and exploration also feature prominently in his narrative.

No Comments